Thirty Saturdays Hath November

When the season ends and the hotel falls still, November becomes our extended Saturday morning. Friends at the table, tools returning to the workshop, dogs to the groomer, paperwork finally faced — and a gentle letting-go of the life we lived before Eddrachilles. A quiet month to breathe, reorder, and begin again.

For most people, Saturday morning is a small weekly luxury — a gentle pause, a chance to catch up with life beyond work. For us, owning and running a small Highland hotel means that during the season, Saturday mornings, along with days off, simply don’t exist.

For thirty-plus weeks of the year, from late March to the end of October, weekends are working days: breakfasts, turnarounds, arrivals, departures, late check-ins, early departures, laundry rhythms, team briefings, bar stock, food orders, reservations, repairs, and the ever-present “just one more” guest request. We don’t resent it — it’s the life we chose — but it means that the usual punctuation marks of the week vanish. No leisurely brunches. No appointments. No gym workouts. No cheering on a team (or offspring) on the sports field. No personal admin. No gentle DIY in the home. And certainly no catching up with friends.

So when November arrives, it feels like a glorious, extended Saturday morning — a month-long exhale after thirty weeks of holding everything together. Hotel business still continues, of course, but our focus shifts to include the more domestic and the wake-up alarm sounds rather later.

This change doesn’t begin the moment the last guest leaves, but only after the closedown rituals are complete: the final deep clean, the ovens scrubbed back to silver, pans poached, the linens stored away, and the last of our seasonal team have headed out for homes or holidays. And then — suddenly — the hotel falls quiet. Corridors that only days earlier echoed with footsteps and conversation now hold a gentle hush. The kitchen, once full of bustle, clatter, loud music and the occasional football commentary (apparently vital to prevent every mother sauce from splitting), settles into a peaceful stillness. After months of rhythm and noise, it is almost startling.

The first morning we wake without an alarm, and without a breakfast service to prepare, has the odd feeling of a bank holiday that comes as a surprise. What do normal people do on a Saturday morning? It seems we take a whole month to find out.

The first wave of November is always friendship. All those postponed dinners and missed celebrations are squeezed joyfully into the diary. Visitors appear — long-overdue, warmly welcomed. Raclette machines are plugged in; dishes from Cook-Up week defrosted and reheated, wine is opened; the conversations stretch late into the night. There is news to exchange from the past half-year (or more), and laughter that grows louder as the room warms and the cheese melts.

Plans for next year arise in that familiar, hopeful way — hill walks, voyages in the Tricia Mairi, small adventures, all promised with great enthusiasm and, depending on the level of merriment, varying degrees of realism. Sixtieth birthdays are already fading memories for both of us and most of our circle but that Saturday feeling makes us all invincible around the fire.

Then comes the domestic archaeological dig. Every November, we rediscover the objects that were removed from the hotel in haste back in April or stored in a corner of our home with the despair of “things we failed to do this winter” — the shoes we meant to mend, the dry cleaning, the boxes of items destined for the loft, including Xmas decorations used last year (why bother putting away now!), the spare couple of restaurant chairs that were stored annoyingly in the hallway for seven months. Contents of wardrobes are sifted through, and we’re oddly grateful to recall which jumpers we actually like and which ones we had quite forgotten existed.

And there is always the annual pilgrimage: dogs and cats bundled into the car for grooming appointments and routine vet checks - local for us so often means travelling right across the UK mainland to the east coast of Sutherland. Garden equipment makes its way to the workshops near Inverness for servicing, the lawnmower given its winter blessing, the strimmer coaxed - or even re-engineered back into life.

The Polycrub and workshop are cleared and reorganised in a satisfying rush of productivity that is entirely impossible during the season. Tools are cleaned, the mysterious missing screwdrivers reappear. Richard’s workshop slowly evolves from “active construction site” to the “place where things belong.” The hotel office becomes less chandlers. Incoming boxes of spring bulbs are sorted according to the masterplan devised back in summer and planted in between the worst of the weather, Dahlias and some more tender perennials are lifted and stored. Mulches are ferried around the ground to help outdoor plants survive the wet winter weather, and flower beds hedges tidied as much as time allows in the ever shortening daylight.

This year there are regular trips down to Lochbroom by Ullapool to Johnston and Loftus boatyard where their team are working on our traditional wooden gentleman’s yacht, Tricia Mairi, restoring her to her classic bonny Miller Fifer origins. The re-masting is progressing well, alongside the building and welding of replacement railings. We are steadily removing her more sailing yacht features installed by a previous owner for a different life than the one she will have here. She may look a little less regatta ready but she is definitely returning to the once proud boast of the famous Miller boatyard in Fife, “boats to get you home”.

Then there is the paperwork. Personal admin piles that have quietly accumulated — letters, reminders, forms, things requiring signatures, things requiring patience. Bureaucrats, in our experience, have never run a seasonal business: their reminders arrive faithfully, regardless of whether we are in the height of summer with guests to care for or in the quiet of November with breathing space at last. So we sit with tea, open the envelopes, and tackle the stack with the grim determination of people who have to face a wall of disapproval for tardiness but are reassured that most of it could have waited until now.

All of this is, however, light relief from the demands of the hotel. VAT returns that need to be done as part of the non-weekend focus of November. Or Fiona’s overdue SEO (what is this AI nonsense?) and hotel website upgrade project which is underway for completion by early January. Let’s consult an expert…oh dear, that will be me.

The routine snagging list of repairs and refurbishments are compiled and scheduled with trades for implementation after their pre-Christmas domestic rush has been handled. Most of all booking enquiries have to be handled swiftly, season 2026’s success depends on those! So amid the relaxation, our month of Saturdays is still fair game for hotel demands.

This year, approaching a decade since we first arrived here, November has brought an additional, unexpected feeling: release. High on the attic shelves sit the remnants of a former life — Jaeger suits, city blazers, and smart shoes from careers that now feel several lifetimes away. Brand names that have all but vanished from the High Street, and so has that chapter from our lives. If these garments haven’t earned their keep in ten years, they don’t belong in our future. Letting them go feels less like discarding the past, and more like acknowledging that our lives — our real lives — are now firmly rooted here, between the hills and the sea.

November is our extended Saturday morning: not quite a holiday but less hurried, restorative, quietly joyful and full of promise. A month in part to reclaim ourselves, to reset our lives, before the wheel begins to turn again.

The Quiet We Keep

Welcoming only children over the age of 12 to stay at Eddrachilles may seem counter-intuitive for a hotel that prides itself on Highland courtesy and welcome. However, the “grown ups” only approach keeps the hotel’s tranquil ambience which is so precious in our busy modern lives.

In the summer this is a gentle place, the sea here doesn’t shout; it murmurs.

Waves brush the stones in Badcall Bay, and on still evenings the loudest sounds are from the seals splashing in the bay.. Eddrachilles was built for reflection — once the parish manse, now a place where people come to rest, to think, and to listen to the quiet.

That quiet has its own gentle rhythm. From the courtyard windows you can watch dozens of small birds breakfasting just a few metres away — the flutter of Goldfinches feasting on sunflower seeds, a pair of Redpolls, a Robin darting in for crumbs. They too like to eat in peace, and their company has become part of the calm that fills the hotel.

That’s why our stays are for guests aged twelve years and over, and why the house and gardens are reserved for residents through the morning and afternoon. It isn’t a rule made against anyone; it’s a promise made for everyone — that guests can read, write, craft, knit, paint, sketch, or simply breathe without interruption.

By evening, the tone shifts. The lights come up in The Glebe Kitchen, local families and neighbours gather alongside our resident guests, and conversation hums across the tables. Children - of all ages - tuck into their suppers with enviable appetite, and the laughter that follows is the sound of belonging.

Quiet doesn’t mean silence. It means space — space for sea and sky, for thought, for creativity, and for one another.

That’s the quiet we keep at Eddrachilles.

A Cook Among Chefs

When the chefs go home and the hotel falls quiet, I reclaim the kitchen for my annual Cook-Up Week — two sides of salmon, a Thermomix, and the comforting chaos of real home cooking in the Highlands.

The season has ended, the hotel closed down, and the local roads no longer ferry guests our way. The last of the team has left this former manse. The kitchen has fallen quiet, and the familiar buzz of The Glebe Kitchen has settled into silence. This is the moment when the professionals retreat — and when I, the resident cook rather than chef, step cautiously (and slightly gleefully) back into their domain.

Every year, as October yields to November, we have what I call Cook-Up Week. It’s part ritual, part housekeeping, and mostly self-indulgence: sorting through remaining items in the hotel fridges, raiding the dry store, and transforming the odds and ends of a busy season into something nourishing — for whoever happens to be around, or for the freezers ready to welcome winter visitors. A last wedge of Highland Fine Cheese, a hefty collection of butternut squash and leeks, a pair of vac-packed duck breasts from the final service. This is the raw material of comfort food.

I am Cordon Bleu chef-trained, yes — a relic of a “just for fun” gap year as I decided which way to go after 25+ years in strategic communication. I can talk fluent classic cookery, price a dish in my head, and negotiate knowledgeably with our food suppliers. I make the occasional restaurateur’s intervention on a menu or pair wines to a dish, but I’m not — and never have been — a chef.

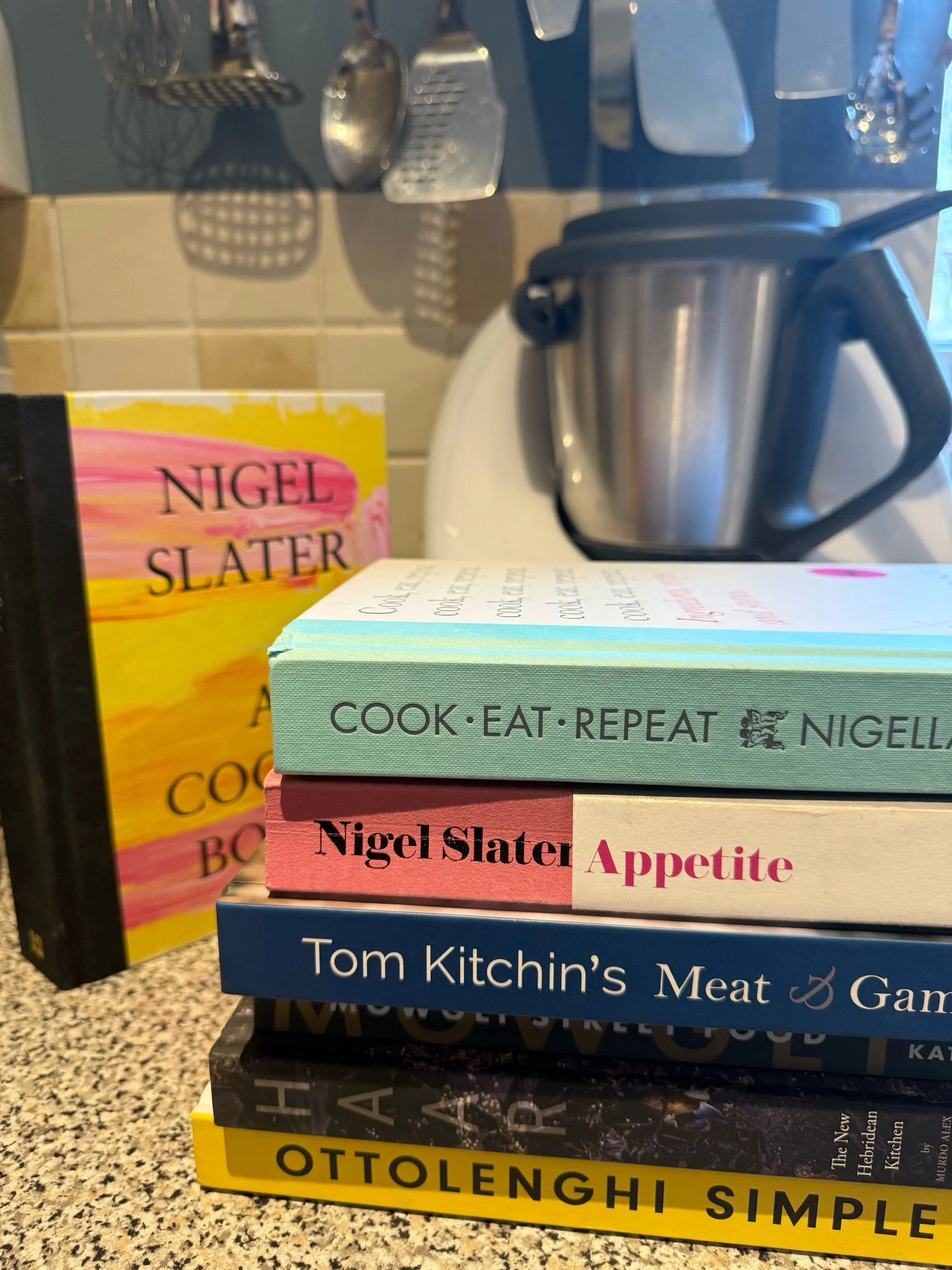

Chefs build structure and rhythm the way musicians build harmony: precise, practised, perfectly timed. They layer flavours with intent, balancing acidity against fat, salt against sweetness, judging heat until every element sings. I, on the other hand, scramble to play by ear. My recipes come from treasured cookbooks, rapid internet searches, culinary academy folders, and whatever happens to be sitting hopefully in the fridge or cupboard. If Nigel Slater would add a splash of cream, I’ll add two; if Nigella says six cloves of garlic, I assume she really meant eight. Consistency in the resulting dishes is something my kitchen has yet to encounter.

During the season I watch Trevor and his colleagues with something like awe. Their craft is deliberate, disciplined, and deeply creative — not just cooking but composition. Every plate that leaves The Glebe Kitchen carries years of practice and hours of quiet refinement: local venison paired with brambles, egg and ham refined as the most glorious Scotch Egg, sauces reduced to a silk sheen. My admiration for that skill is endless. Which is precisely why, once the last dessert has been served and the chef’s whites are laundered for the year, I rather enjoy lowering the standard to something altogether more homely.

This year’s Cook-Up Weekend began with a small comic drama. A supplier, bless them, forgot that our standing order had been cancelled until April — delivering not one but two sides of the finest Scottish salmon. For a moment I considered sending them back — but the temptation was too strong. They now lie in the fridge like a challenge, glistening with potential. Shall I poach one in white wine and herbs, or cure it with the last of the Polycrub dill and blackthorn sea salt for a touch of Nordic theatre? The truth is I’ll probably do both, purely in the interests of research, and throw in the occasional Lime and Coriander Salmon Kedgeree for a comfort supper (thanks, Nigella).

Then there was the large portion from a truckle of Arran Cheddar, equally unintended, equally irresistible. I’m pretending that it’s being saved for Christmas, but already I’m circling it like a cat around cream. Can I resist until December? Unlikely. Some temptations are simply not designed for endurance.

And speaking of indulgence — one of my chief delights each winter is reclaiming possession of the Thermomix. Back in 2015, when Richard and I finally decided to get married, he gallantly offered to buy me an engagement ring. As a cordon bleu student at the time, I replied, in perhaps my most cheffy moment ever, “I’d rather have a Thermomix.” He obliged. Not long after, when we arrived at Eddrachilles, I realised my pride and joy would have to be placed at the disposal of a rather lightly equipped hotel kitchen. So, each October, I reclaim it like a long-lost friend. This year we treated ourselves to an upgraded model, and I can’t wait to put it through its paces. Used properly, for a solo cook it’s like having the best ever commis chef — one that’s never late or hungover, never steals your fish, and never gives you lip. It even makes a decent Hollandaise or porridge, lump-free and perfectly behaved.

Of course, not every surprise delivery or gadget can solve the perennial mystery of surplus black pudding. We appear to have acquired a heroic quantity of it this year — far more than any sensible household could possibly consume. It has therefore become a creative challenge: breakfast fry-up, lentil soup, baked potato topping, even an experimental pasta dish that should probably never be mentioned again. There are limits to enthusiasm, even mine.

Yet that’s the quiet pleasure of Eddrachilles winter cooking. It isn’t about presentation or performance. It’s about rescue and reinvention — the alchemy of turning leftovers into something that feels generous and deeply satisfying. The professional kitchen runs on precision and timing; the winter kitchen runs on instinct and appetite. Both matter. Both feed us, in very different ways.

So over the coming months the food at Eddrachilles will look very different. Less “plated” and more “piled.” Bowls of soup deep enough to wrap your hands around, slow-cooked stews that scent the whole house, soda bread warm from the oven, baked apples filled with whatever spices I can find in the back of the cupboard. Meals that are shared rather than served, timings dictated by the rhythm of our shortened days, eaten by candlelight while the wind shakes the windows and the sea murmurs on the shore below.

And when March comes round again, I’ll hand the kitchen back to those who truly earn the title of chef. Trevor and his team will return with their calm choreography, their precision knives and refined flavours, ready to open another season. Until then, the kitchen is mine — smaller, slower, humbler, and very content.

There’s room in every kitchen for both craft and comfort, for chefs and for cooks, for flair and for heart. This winter, I’ll be cooking, not cheffing — and loving every moment!

Written by Fiona Campbell Trevor — Highland lady hotelier, seasonal cook, pet slave, and firm believer that butter improves almost everything.