A House, Built for Service and Witness

This simple Highland home has been shaped by the lives lived within it — not as legend or folklore, but as memory layered over time.

The original building, still the core of Eddrachilles Hotel, was built in the early 1800s as a manse — the home provided for a parish minister of the established Church of Scotland (Presbyterian). Despite its quiet and peaceful location, this building has been witness to periods of great turmoil and hardship for Northwest Highlanders

A manse — from the Latin mansus or "dwelling" — formed part of the established infrastructure of the parish, alongside a parish church and school. In Presbyterian Scotland, a manse was never intended to be a private retreat. It was a working household, expected to support the minister's pastoral duties to congregation and community alike, providing a middling standard of living rather than comfort or wealth. The emphasis was on the learned rather than the wealthy. It was also the place where sacraments might be performed in simple ceremonies rather than in the church: baptisms and weddings among them.

-

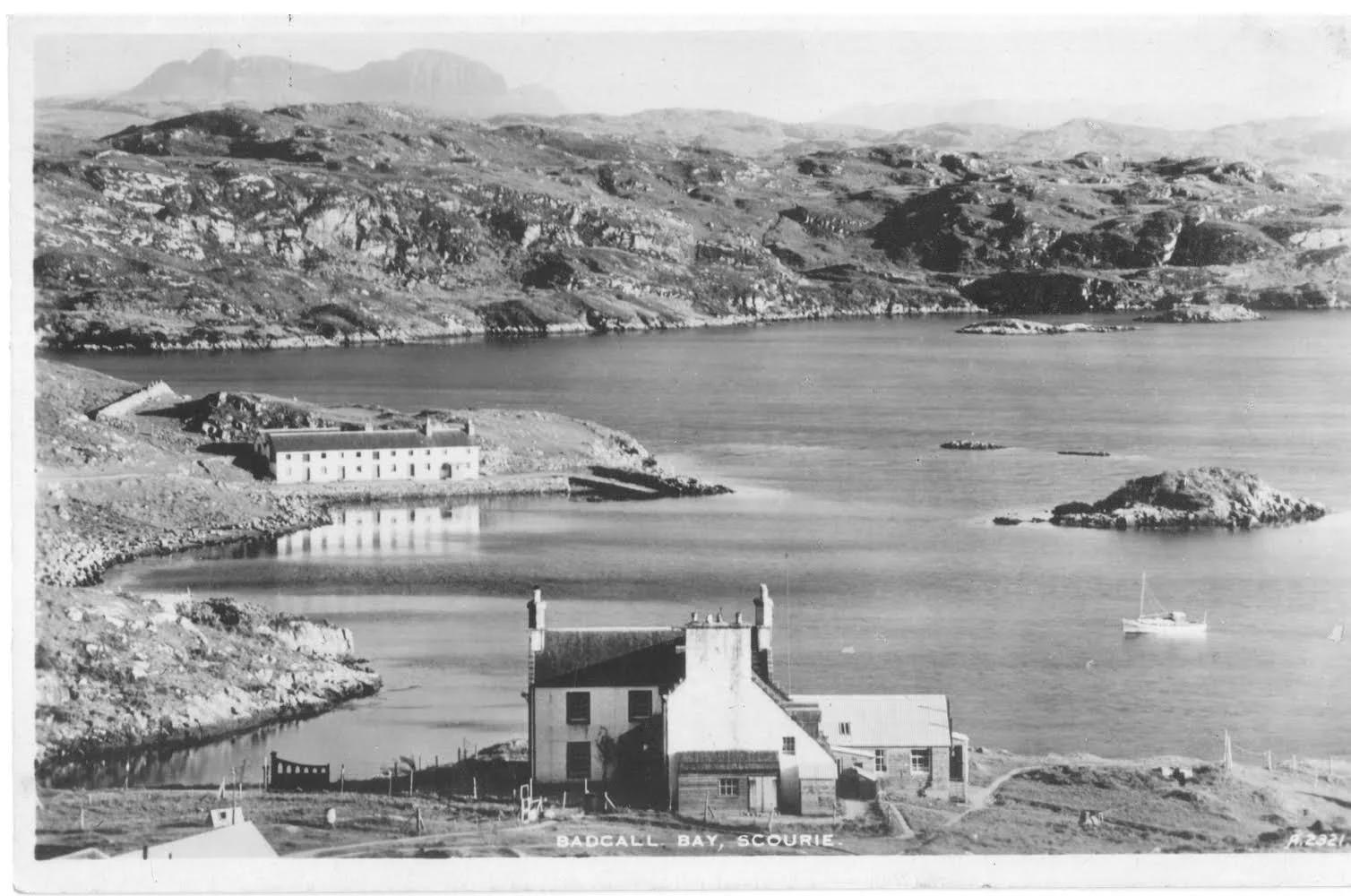

The parish of Eddrachillis was created in 1724, part of a division of a much larger parish. A simple church with a heather roof was erected at Badcall, and old estate maps show references nearby to an “old manse” to the west of the church. It is likely that there was a basic property in that location which was later replaced by a larger white building (mentioned in the Admiralty Waymakers), a successor manse which much later became Eddrachilles Hotel.

This more substantial manse was intended to serve the Eddrachillis parish, between the Kyle of Laxford and Kylesku. The parish was closely linked to Assynt and the natural harbour in Badcall Bay was widely used. Farmland, although of poor arable quality, was available. As a consequence, Badcall was at this time chosen over Scourie as the location.

The manse at Badcall and its associated lands were gifted by the Duke of Sutherland, alongside a programme of church building in the Highlands founded by the Hanoverian Government in the aftermath of the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745–46.

While few traces remain of the earlier manse, There may have been earlier ecclesiastical accommodations in the immediate area as a simple church building with a heather roof was established in the 1720s and, although turned into a holiday home in the 1970s, the white building with its slate roof is still identifiable from the A894 immediately north of the turning for Eddrachilles Hotel (look for the simple bell tower on its western side).

Attached to the house was a glebe: land legally assigned to the parish to help sustain the minister and his family. In practical terms this made the manse akin to a smallholding, with gardens, pasture, and outbuildings managed either by the household itself or by a grieve. The arrangement reflected an expectation that the minister's life would be of middling standard and rooted in the daily rhythms of the place he served.

At Eddrachillis the glebe was larger than many, possibly a necessity in a remote parish where much of the land was rough grazing rather than fertile ground. The eventual holding included ground close to the house and, unusually, extended into the bay itself with one of the islands. There is some evidence that the lands may have been consolidated in several phases.

Taken together, house and glebe made the manse a place of service rather than comfort alone — a household shaped by responsibility, endurance, and close connection to its landscape.

“The house remained a working centre of parish life — shaped by duty, endurance, and adaptation rather than comfort alone.”

Lives Lived Here

Life in a nineteenth-century Highland manse was organised around work as much as worship. At the manse for Eddrachilles parish, the household combined domestic life, pastoral duty, and the management of the glebe. The manse functioning as a semi-public place of residence rather than a private home.

-

The glebe dictated much of the lives lived within the manse. At Eddrachilles it supported a mixed pattern of cultivation and grazing typical of the Highlands: enough arable ground and livestock to sustain the household, with labour shared between family members, a grieve for larger glebes, other servants, and hired hands. This work reduced dependence on cash income and tied the rhythms of the manse closely to season and weather. The minister might inspect stock or fields as readily as he prepared sermons or correspondence, while pastoral visiting often required long journeys across a scattered parish.

Within the house, the minister's wife carried primary responsibility for managing the household. Fuel, food, a cottage or kitchen garden, dairy produce, clothing, servants, and the care of frequent visitors all fell within her domain, assisted if fortunate by the daughters of the manse. Hospitality was not optional; manses routinely hosted clergy, teachers, officials, and relations, often stretching modest resources.

Lives beyond the manse

The nineteenth century brought turmoil and profound change to Highland society. The manse would have been witness to much of this alongside individual family tragedies such as drownings of fishermen in the Bay.

Early 19th Century - ollowing the destruction of the clan system after the failure of the 1745–46 Jacobite rebellion, landowners in the early 1800s moved swiftly to "clear" the Highland glens of homes and smallholdings to introduce sheep farming. Sutherland saw some of the most brutal clearances, including those led by the infamous Patrick Sellar and the fire-raising of 1814.. At best those cleared to the coast were offered crofting strips on poor land. For others there was “assisted emigration”, often to very uncertain futures in the colonies including Nova Scotia, Cape Breton, Australia….

After 1815 and the end of the Napoleonic Wars, tariffs were removed and British markets were flooded by cheaper European products crushing local industries. For Highlanders, the collapse of cattle trade and kelp industry (iodine) brought further hardship.

Mid 19th Century - The Improvements”” initiated by landowners to create increase efficiency in form their estates. These were carried out by Factors/Estate managers, including Evander McIver who was based in Scourie Lodge serving the Duke of Sutherland. It meant further displacement of Highlanders. consolidation of small holdings into farms, and higher rents for those who remained. Other moved to the new cities to take up work created by industrialisation.

-

Displaced families moved to coastal settlements such as Scourie on the west coast or Helmsdale on the east. In the decades that followed, the programme of improvements continued, but sadly not to the benefit of the displaced.

In Northwest Sutherland, from 1837 the implementation of these changes was directed from Scourie Lodge, where the Duke of Sutherland's factor, Evander McIver, was based. Although not part of the notorious burnings, his reputation is forever associated with the unrelenting consolidation of land for new agriculture to the benefit of the landowner. He was also a strong advocate for emigration, presumably believing that those sent overseas would have better opportunities. He played a key role in enabling the victims of the potato famine on Handa Island and nearby areas to be “voluntarily cleared to Nova Scotia”. Whatever his intentions, in reality they faced remitting hardship and poverty in North America, an experience repeated countless times

While the Church was not an instrument of clearance, it was a clearly witness to the suffering and poverty inflicted. For many ministers the association with the landowners through patronage became untenable. Combined with new and bold theological thinking in the 19th century a schism was almost inevitable and with it profound changes for the church and manse at Badcall.

Church Going - 1843

While the manse at Badcall was undoubtedly busy and valued by parishioners, its role as the parish manse was ultimately short-lived. Amid many social changes, the religious upheaval in Scotland of the 1840s was felt keenly here.

During the Great Disruption of 1843, the parish minister living at Eddrachilles in Badcall, the Reverend George Tulloch, left the Established Church to join the Free Church, followed by almost the entire congregation. He resigned his stipend and residency at the manse in Badcall. It was regarded as the most complete Disruption shift of any Highland parish. His reasons were specified as religious — he was strongly evangelical — and his opposition to patronage.

-

For a time, the breakaway parishioners held services in makeshift settings including a tent sent by the new Free Church in Edinburgh. When that was wrecked in a storm, the parishioners used what are still referred to as the Worship Rocks. The Free Church of Scotland then built a new church and smaller manse in Scourie in 1845. Religious focus shifted to Scourie.

Through these changes, the building at Badcall remained a working centre of parish life, becoming more obviously a glebe farm. However, the appointment of ministers is not well recorded and may have been relatively short-term while the Church worked out what could be done alongside other schisms in the Presbyterian Churche

First World War and Changes in Ownership

In 1916, after some years of uncertainty, the old manse was finally bought from the Church of Scotland by a hotelier from Ullapool. Having transferred from ecclesiastical use into private ownership not much seems to be known about the next decade. . However, in 1929 it was purchased by Lt Col Thomas Wilkinson Cuthbert, a former estate manager and First World War hero from the Seaforth Highlanders, as his home for his retirement.

-

At the outbreak of war in 1914, the 4th Seaforths had been among the first TA units to be called into active service and sent overseas. In one battle, despite a head wound, the then Major Cuthbert assumed command of the 4th Seaforths when his Colonel was killed by enemy fire. He retained his battlefield promotion and was award several medals in recognioin of his bravery.

His decision to settle at Eddrachilles in the post-war years brought the house into a new chapter.. Alongside managing the estate, he worked to preserve the records and memorials of his battalion, ensuring that its service and losses were not forgotten.

Cuthbert died in 1936 and is buried here, overlooking the sea. His grave lies within the woodland grounds, and his presence is still acknowledged in the naming of The Colonel’s Dell and The Colonel’s Lounge — a continuity of remembrance rather than a monument.

Second World War in Northwest Sutherland

During the Second World War, the West Highlands played a vital but secret role in the national war effort. Not only was much of the coastline subject to restricted access, and the surrounding waters and hills were used for training and preparation, for some of the Allies’ most daring campaigns, including the training the brave young men who became Human Torpedoes in the waters by Kylesku.

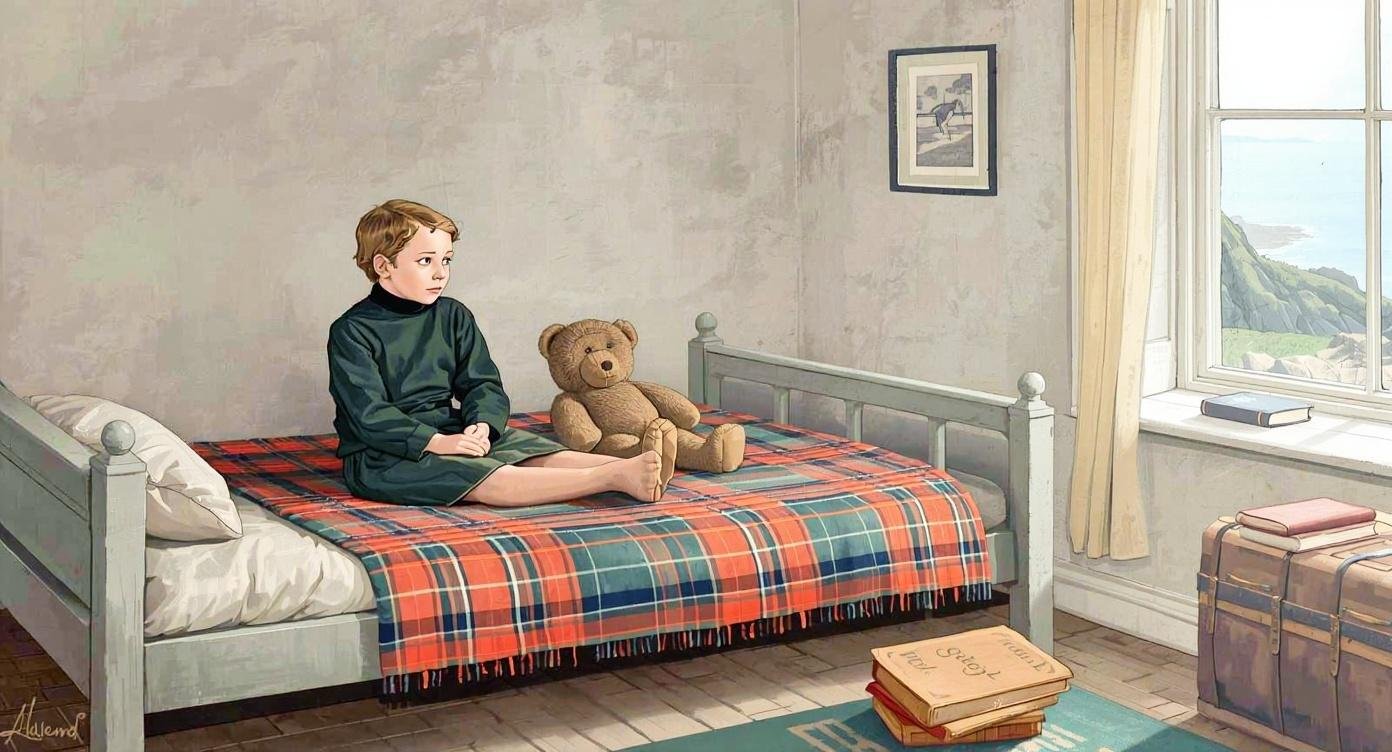

The former manse continued as a family home, stewardship passing to the late Colonel’s relatives. Some children in the extended family were evacuated here from time to time to escape the worst of the Blitz in towns and cities. It must have been frightening and disconcerting to be in a such a remote settings with distant relatives but at least rationing was softened by rural living and access to land. Everyday life continued alongside wartime operations, and those in this parish learned, as so many did, to see much and say little.

-

In the years immediately after the war, with ownership held in trust and no direct heir, the house passed through a period of transition. For a short time the former manse and associated buildings operated as a Youth Hostel, a chapter still remembered by some former visitors and their families. Eventually, the legal processes and the property could be sold becoming once more a private family home.

Roads, Access, and a Hotel

For much of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, access to this part of north-west Sutherland depended on a combination of narrow single-track roads and the ferry crossing at Kylesku. These routes were adequate for local movement, but they limited wider travel and made the area feel distant, even within the Highlands.

That began to change in the later twentieth century. From the 1970s onwards, a programme of road improvements gradually created a continuous north–south route along the west side of Sutherland and Assynt. The replacement of older, winding roads and the eventual construction of the Kylesku Bridge in the early 1980s removed the final bottleneck, transforming access to the region

-

For Badcall, this shift proved decisive. During the road works, the house accommodated engineers involved in the project, and the income from that period enabled a single, definitive transformation. In the early 1980s, a sympathetic extension was built, adding eight new ensuite bedrooms and allowing the house to operate fully as a small hotel rather than a seasonal letting. A sun lounge followed later, extending the building’s relationship with its setting.

In the early twenty-first century, the Wood family retired from the hotel business, and the former manse — by then firmly established as a hotel — was sold with a small area of surrounding woodland. The walled garden and remaining glebe land were retained separately and later sold in 2013. The present setting reflects these later changes: a historic house adapted for hospitality, set within its immediate landscape rather than the wider agricultural holding that once sustained it.

Improved access did not alter the character of the place overnight, but it changed what was possible. A house shaped by centuries of service and domestic life entered a new phase of hospitality, suited to a landscape now open to those able to reach it.